The bus station always smelled like burnt coffee and wet wool, even on a night that was supposed to taste like champagne. A tiny TV bolted into the corner played the Times Square feed on mute, confetti already collecting like snow in the gutter of the screen. Beneath it, a vending machine wore a faded American flag magnet—crooked, sun-bleached, stuck there by somebody who’d needed a reminder that they were still part of something.

I sat on a hard plastic bench with two suitcases at my feet and my grandfather’s pocket watch open in my palm, feeling the steady tick through my skin like it was trying to keep me from drifting away. My one-way ticket to Chicago—$127—was folded so tight the paper had creased into a sharp little weapon. My phone buzzed again.

I didn’t look. Somewhere, a crowd was screaming “Happy New Year.”

I was counting seconds like they were the only thing I still owned. “Sir,” a voice said softly.

“Are you okay?”

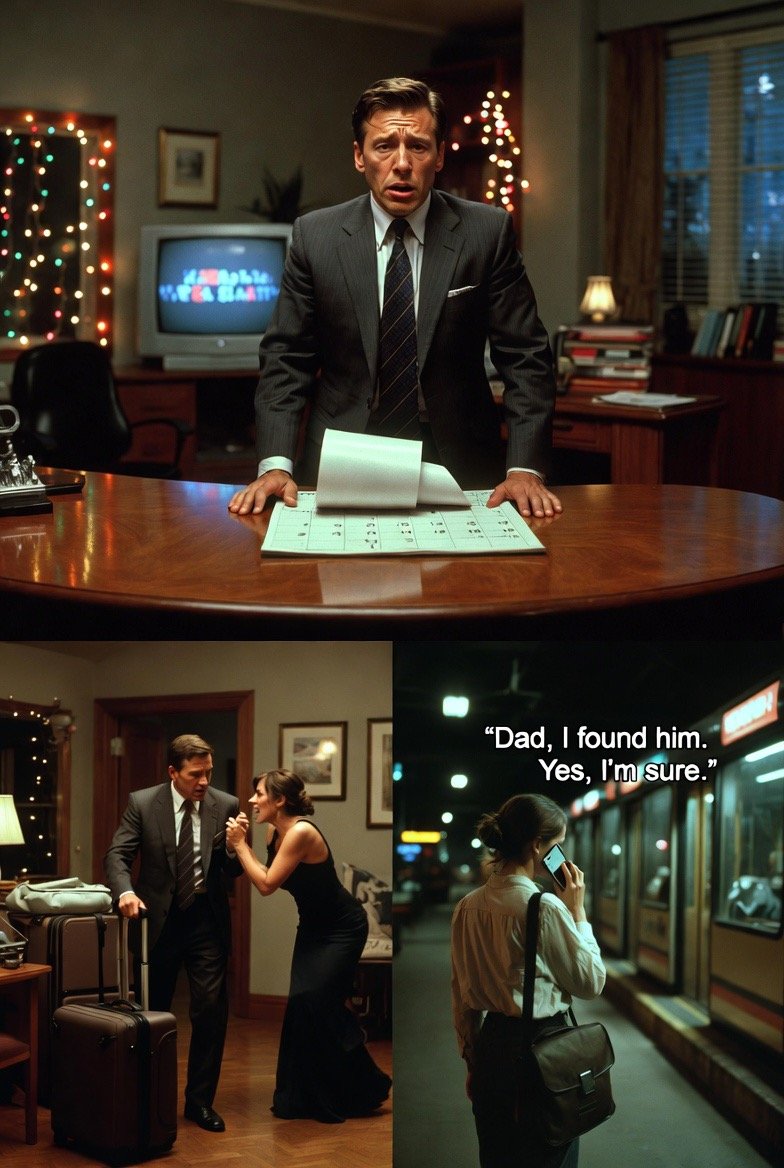

I looked up at a young woman with a ponytail, a messenger bag, and eyes too awake for after midnight. I tried to lie. My throat refused.

When I told her the truth, she didn’t gasp or pity me. She pulled out her phone, called someone, and said, “Dad… I found him. Yes.

I’m sure.”

And just like that, the new year stopped being theirs and started being mine. That night didn’t begin at the bus station. It began hours earlier under a chandelier that cost more than my first car.

Richard Pembbrook’s New Year’s Eve party was always a performance. Not a warm family gathering—more like a live demonstration of what it meant to belong to his world. Sinatra played low through hidden speakers.

The champagne was imported and already chilled to the perfect temperature. The shrimp cocktail sat in a crystal bowl like it was posing for a magazine. Every guest had the same polished smile and the same careful laugh that said, I’m important enough to be here.

I’d learned how to wear that laugh, too. Thirteen years at Pembrook Industries will teach you a lot about survival. I had just finished helping an older board member find the bathroom—because even at a party, I was still the guy who fixed problems—when Richard’s hand appeared on my sleeve.

Two fingers. Not a grip. A hook.

“Trevor,” he said, and it wasn’t my name so much as a summons. “Come with me.”

He didn’t smile. He didn’t offer me a drink.

The story doesn’t end here –

it continues on the next page.

TAP → NEXT PAGE → 👇